Africa’s Informal Transportation – The Rise and Challenges of Africa’s Popular Means of Travel

Africa’s rapid urbanization has resulted in several mobility issues. To cater to these challenges, innovative transport infrastructure in the form of informal transportation (sometimes called paratransit) has emerged. These informal transport are in the form of minibusses, motorcycle taxis, and shared cabs with different names across the continent. Although these transport systems, which are shadows of state and urban planning failures, serve hard-to-reach areas more conveniently and cheaply than planned transport systems, they are fraught with other problems. As a result, many African cities have supported plans to formalize and revamp the transport system but with limited success.

Many African cities lack a reliable public transport system. Informal transport (sometimes called paratransit) has been an excellent replacement — carrying millions of people daily. The easiest way to get from A to B in many African cities is by taking informal public transportation. But how do you define ‘informal’? This blog explores the topic and shows you these different informal transportation modes in Africa.

Danfo Buses, a form of informal transport in Lagos-Nigeria (Photo from Washington Post)

Informal public transportation in Africa emerged as a relatively new form of transport in the 1990s, and its popularity has since grown rapidly across the continent. They include minibusses, vans, lorries and also private cars that have been converted into taxis. These vehicles offer flexible services to residents who can’t access conventional public transport networks. They are often cheaper than private taxis, which have set rates and make them unaffordable.

The term ‘paratransit’ refers to flexible transportation systems that supplement regular public transport services such as buses, trams, and trains by giving travelers more options on how and where they want to travel to, who they want to travel with (e.g., traveling alone or with a group), their preferred departure times and the types of journeys they want to take (e.g., one-way or return trips). Paratransit services can be categorized into three broad groups: demand-responsive transit (DRT) systems, share taxis, and jitneys (also known as shuttle buses). It is used by African travelers and commuters between urban hubs, towns, or intercity destinations.

The informal public transit systems in Africa are a fascinating phenomenon. Ranging from bicycle taxis and pick-up trucks to good old walking, these methods of transport play essential roles in Africa’s economy and social fabric. The informal modes of public transportation are pervasive and available in large cities like Dar es Salaam, Mombassa, and Kigali. Most Africans depend on informal transportation to get everywhere: work, school, shop, etc. In addition to being used as public transportation, bikes are also a mode of transport for leisure activity. They are found across Africa and utilized by people of all ages, wealth statuses, and ethnicity. These are different from the formal public transport systems of Europe, North America, and Japan.

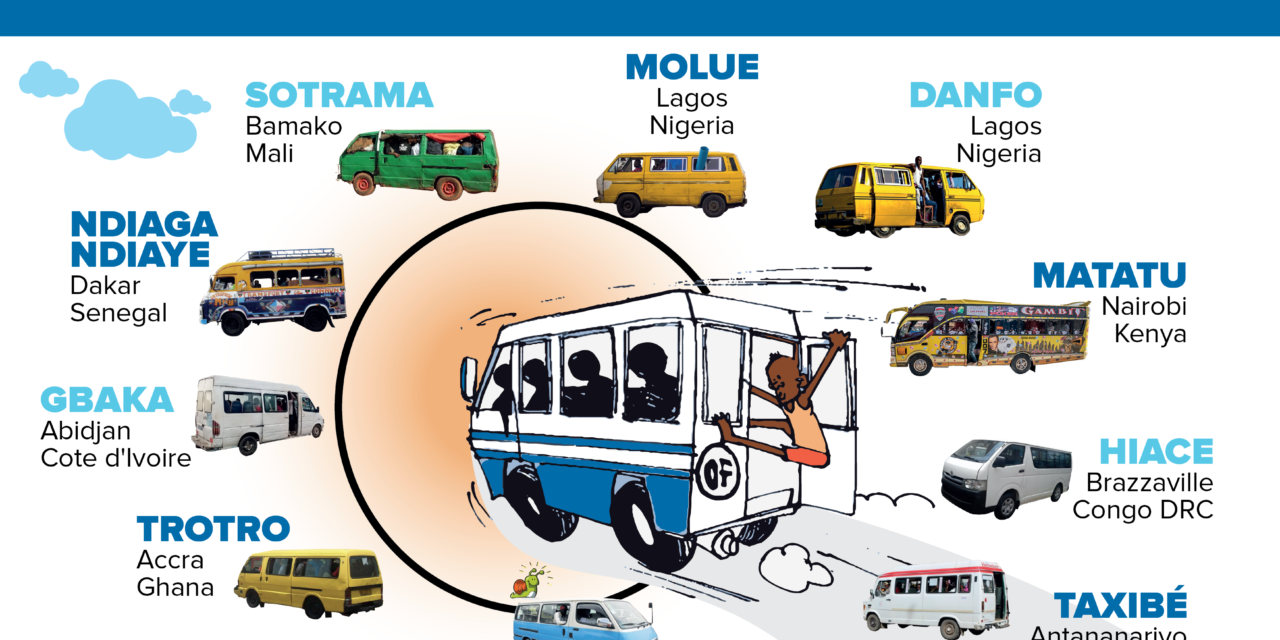

There is a wide variety of informal transport types within African countries, including shared taxis and buses, minibusses, and motorcycle taxis.

Informal transport use vehicles that are not fixed to the track. These informal systems are locally or regionally known as moto-taxis, phycal, matatus, sept-place taxis, tro-tros, coasters, keke, danfo, okada, boda boda, and so on. These include shared taxis and buses, minibusses, and motorcycle taxis.

Shared taxis and buses are most common in Africa, where they can be found on most major roads throughout many different countries. Shared taxis are often referred to as commuter trains or informal transport, depending on their location in the city or country. They should not be confused with private taxi cabs, which offer a similar service but charge higher fares and operate independently of state-owned companies.

Motorbikes for informal transport in the city of Freetown (Photo from Africa Daily News)

Informal transport vehicles are smaller than mass transit buses and have a more flexible route. They are usually not bigger than 18 seats and are typically vans or mini-buses because they’re easier to drive through traffic. They meet the demand for transportation over short distances, such as within cities or townships where there may only be one route available from place A to B (e.g., from the airport into town). The cost per person can vary depending on how many passengers are traveling together distance, among others. These vehicles do not follow official schedules and are often the cheapest way for someone to get from point A to point B.

Informal transport has no standardized schedules, and nobody makes sure that it runs properly.

The typically unregulated and unlicensed informal transport is usually cheaper to travel with than formal public transport. Because it is less expensive than a taxi but more expensive than public transport, it can be an especially helpful option for those who aren’t able to afford the full price of higher-quality public transport but may still need it for some of their trips.

Informal Transport Organizations

Several African countries have established informal transport organizations to help commuters. For example, Morocco has set up routes for its informal transport service across the country’s cities. Within these cities, there are designated local stops where passengers can wait for the van to pick them up and drop them off at their desired location. These services cost between one and three dirhams per trip–the equivalent of about $1 USD–and are generally run by private companies or individuals who own their own vehicles (rather than being provided by the government).

Informal transport organizations are run as unregulated enterprises by individual entrepreneurs with no government intervention.

- Informal transport organizations are run as unregulated enterprises, with no government intervention.

- There are no laws to govern informal transport organizations.

- Drivers operate on their own and usually do not have official operating licenses.

- They are often run by entrepreneurs who are only interested in making money.

Dala-Dala buses Dar-es-Salam Tanzania (Photo from CNN)

Challenges of Informal Transport

Informal transport offers a unique transportation experience with regard to crowding and safety. These are particularly unique with regard to crowding, as they are generally not crowded at all. For example, motorcycle taxis (also known as okadas) have become popular in African cities because they can travel through gridlocked traffic that would stop any other vehicle like cars or buses dead in its tracks! Only two people can ride on each motorcycle taxi. As they have the capacity to go around traffic and avoid congestion, they are typically faster than other forms of transport. However, these can be quite dangerous for both riders and pedestrians (especially in already chaotic traffic conditions). Some critics claim they are arguably the least safe form of public transport in Africa; especially for women or children who may be riding alone.

Despite some benefits, informal transport pose many challenges to its users.

It is important to note that while these modes of transportation do make commuting easier for those who live outside urban areas without access to regular public transport services; they also pose some significant safety concerns due to both human error and reckless driving practices among some operators who feel pressured by competition against other companies. Unfortunately, informal transportation services also have a bad reputation for high traffic violations that make using them very dangerous. Due to the perceived unsafely of informal transport, critics have called for some regulation. There have been large-scale unsuccessful attempts to formalize informal transportation in many African countries. However, advocates have suggested that these are essential; the inability of governments to provide reliable transport to the populace lends to the growth of these forms of transportation.

The Future of Informal Transport

The informal transport systems in Africa are difficult to navigate, but nonetheless a necessity for those who have no other option. They are efficient and effective ways to move people around the African continent. Not only do these vehicles cover more ground than your standard bus or taxi, but they also offer more affordable fares that are suited to a wider audience. This type of public transportation isn’t going anywhere anytime soon; in fact, its appeal is likely to grow as many African cities urbanize. Even in cities where Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) is being adopted to formalize informal transport, it’s likely that the informal transport will be deferred to other corridors, so it will be better for cities to develop a mix of BRT and Informal transportation.

At the end of the day, it’s easy to take public transportation for granted. And if you don’t have easy access to this type of transportation, then you know that it can be a daily struggle. However, if you live in any of the places in Africa then you more than likely don’t have many other options when it comes to getting around. In places where formal public transportation is not readily available, people simply have little choice but to use informal roadside transportation services in order to get around.

Read Also: Here is why Africa’s transport system is underdeveloped

Informal Minibus and mini-cycles in Kampala Uganda (Photo from City Fix)

It is interesting to see the different methods Africans developed for getting around. It could provide inspiration for future transportation solutions in urban areas. By understanding the informal nature of transit in Africa, and by not letting that inform design, Africans can come up with prototypes that can be used to improve transport infrastructure. They could even further embrace the informal nature of transit by creating designs that make it easier for drivers to incorporate into their existing business practices.

**Further reading: This article highlights the concept of informal transport/paratransit and these are some examples in African cities.

Questions for thought

Can we support and regulate these informal transport systems to the point where they are more efficient for users, safer for passengers, and less damaging to the environment?

How do you go about formalizing a transport system that has been operating in the informal sector for decades?

****Featured image source: Africa Kitoko

Thanks for another fantastic article. Where else may anyone get that type of information in such a perfect manner of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and I’m on the look for such info.

I appreciate your saying that there are three main categories of paratransit services: demand-responsive transit (DRT) systems, share taxis, and jitneys (also called shuttle buses). My sister claims she wants to provide DRT systems for employees going on business travels. I’ll provide her with experienced guidance on paratransit operations to assist her.

I’m not that much of a online reader to be honest but your sites really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back in the future. Cheers

Oh mmy goodness! Impressive article dude!

Thanks, However I am experienxing treoubles withh your RSS.

I don’t khow why I can’t subscibe tto it. Is there

anyone else having thhe same RSS problems? Anyone who knbows thhe answer ill

you kindly respond? Thanx!!